|

|

RISE AND DECLINE OF WILLOW GROVE PARK

By DR. HAROLD E. COX

Associate Professor of History, Wilkes College

Paper read before the Old York Road Historical Society, March 19, 1963,

in Musicians Hall, Grace Presbyterian Church, Jenkintown, Pa.

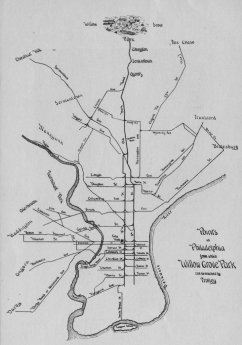

We CAN identify three well-defined stages in public transportation in the great cities -- from the 1850's until 1865, from 1865 to 1890, the era of the horse car, and the frenzied expansion in electric railways from 1890 until about 1905.

All were enthusiastically promoted by speculators, as well as by many public-spirited businessmen, and the usual result was over-expansion, losses, and receiverships. Faced with these problems, the traction magnates turned to building suburban lines, and to promote weekend traffic many established amusement parks in the suburbs of the cities.

Within the Philadelphia area there were four of these Woodside Park, on the fringe of Fairmount Park, Point Breeze Park, the last to be established and the first to expire, Erdenheim, at Chestnut Hill, and Willow Grove, the subject of this sketch.

None of the first three could compare in size and importance with Willow Grove Park. In its day, it was looked to as a model of what the properly operated park should be, and was held up as such by such authorities as the Street Railway Journal, which covered its activities extensively and thoroughly. There can be little doubt that this operation was the inspiration for many similar undertakings throughout the country.

The construction of the park had its origin in the plans of a group of Philadelphia promoters who, in 1892, incorporated the Philadelphia, Cheltenham and Jenkintown Passenger Railway Company, for the purpose of building an electric street railway from 15th and Erie Avenue in Philadelphia to a point which was described as being between the Valley Road and the Philadelphia, Bound Brook and New York Railroad, in the borough of Jenkintown, the line to follow Old York Road for its entire distance.

The original intent of the incorporators is not clear from the material available, but it seems likely that the company was merely a front for the Philadelphia Traction Company. This company, dominated by the Widener and Elkins interests, was the largest in Philadelphia. Still, it had difficulty competing for park and suburban traffic with the Peoples Traction Company, a much smaller undertaking which controlled vital suburban lines, especially the Germantown Avenue line, and a major cross-town route which ran from Kensington and Frank-ford to Fairmount Park via Girard Avenue.

The Peoples Traction Company apparently had no intention of losing this new suburban route to Philadelphia Traction without a struggle. The Philadelphia portion of the P. C. and 3. was authorized by ordinance of Philadelphia City Council on June 29, 1893, but a competing company, known as the Old York Road Passenger Railway Company, clearly controlled by the

Peoples Traction Company, secured an overlapping franchise from Erie Avenue to Broad and Olney only four days later. It appeared that the competition for the route could easily lead to acts of violence, as it already had elsewhere in Philadelphia, if both companies decided to begin construction simultaneously.

Peoples Traction Company, secured an overlapping franchise from Erie Avenue to Broad and Olney only four days later. It appeared that the competition for the route could easily lead to acts of violence, as it already had elsewhere in Philadelphia, if both companies decided to begin construction simultaneously.

It is difficult to assess what actually happened. No records survive of the Old York Road Company, while the P. C. and 3. makes no mention of conflict or competition in its relatively dull directors' minutes. It seemed to be expending most of its energy during this period in nailing down every available thoroughfare, through franchise grants.

In the city of Philadelphia this included a franchise on Mill Street and the Limekiln Pike north to City Line, and then on into Glenside along a route which paralleled very closely the route finally constructed in 1905 along Ogontz Avenue. Another franchise which followed Fishers Lane and Olney Lane to the Old Second Street Pike, now Rising Sun Avenue, and thence to City Line, came into direct conflict with the line of the Electric Traction Company being constructed from Franklinville to Fox Chase, and was probably never taken seriously by anyone concerned.

Outside of the city it secured in March, 1894, a franchise in Jenkintown to build on Summit Avenue, Leedom Street, Elm Avenue and York Road north to the Borough line, the indication that it planned to extend further North.

While the activities carried on as late as March, 1894, therefore, indicated a company which had good intentions of constructing a line, even though they as yet had little to show but franchises, there was obviously something going on behind the scenes. Without warning or explanation, the Board of Directors' minutes for April 9, 1894, report the mass resignation of the entire board of directors, and its replacement with an entirely new board headed by George Shelmerdine, a power in the Peoples Traction Company, and the Philadelphia Traction Company completely lost influence within the Company. On August 29, 1894, an agreement was signed between the P. C. and 3. and the Peoples Traction Company, which undertook to construct the line and operate it as lessee.

One can only guess at the reasons for the abrupt change. Whatever the reason, Peoples Traction acquired firm control, and also acquired title to the Cheltenham and Willow Grove Turnpike, which controlled the Old York Road, and operated it as a toll road. This latter company, established in 1803, was the oldest underlier of what eventually came to be the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company.

Construction of the line began in 1894, and was pushed in-to the winter season. The construction of the line through territory which had up until that time had no public transportation was beset with problems. The long distances involved brought about problems of electrical transmission, which were resolved by building a large power house in pseudo-Spanish style in Ogontz, near the corner of Old York Road and Forrest Avenue. Peoples Traction acquired new equipment to operate the line, and finally, on January 24, 1895, opened service from 4th and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia via 8th, Germantown and Old York Road to a loop built in Forrest Avenue and on the property of the power station.

After the spring thaw had permitted the resumption of construction, service was extended North to Willow Grove on May 11. During the first summer of operation, traffic was stimulated by the purchase of one hundred acres of land at the end of the line in Willow Grove, which was used for a picnic ground. The picnic ground shortly was expanded to include a general amusement park, emphasizing entertainment of a cultural nature, a radical departure from the Coney Island approach to the problem,

usual in most American cities.

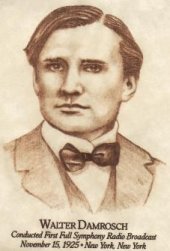

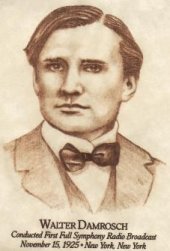

Willow Grove Park was opened for the 1896 season, and immediately generated additional traffic, although not nearly as much as the management had hoped. Deciding that still greater attractions were needed, in 1897 the Union Traction Company (Peoples Traction having been taken over the previous year), decided to institute regular music programs in the Park, and hired the New York Symphony Orchestra to come to Willow Grove and play the entire season in the band shell, under the direction of its conductor, Walter Damrosch. So popular was this feature that it was retained, and the musical presentations of the Park became its most famous attraction.1

usual in most American cities.

Willow Grove Park was opened for the 1896 season, and immediately generated additional traffic, although not nearly as much as the management had hoped. Deciding that still greater attractions were needed, in 1897 the Union Traction Company (Peoples Traction having been taken over the previous year), decided to institute regular music programs in the Park, and hired the New York Symphony Orchestra to come to Willow Grove and play the entire season in the band shell, under the direction of its conductor, Walter Damrosch. So popular was this feature that it was retained, and the musical presentations of the Park became its most famous attraction.1

Over the season, the interest of the public in a single musical group tended to wane. In later years, therefore, the Union Traction Company, and its successor, Philadelphia Rapid Transit, diversified the offerings, and brought in musical groups for stands which ultimately averaged two weeks.

In the early years, Walter Damrosch and his orchestra remained the mainstay of the Park, but a variety of other organizations were hired, including such diverse offerings as the Chicago Marine Band, the Royal Marine Band of Italy, Creatore's Royal Italian Band, Victor Herbert's Orchestra, and the band of John Philip Sousa.

Over a period of years, marked preference was shown by both the management and public for certain groups. Probably because of the acoustical problems inherent to outdoor concerts, bands were far more popular than orchestras, only Victor Herbert and Walter Damrosch being able to consistently hold their own in the latter category.

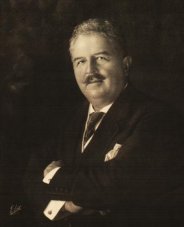

Of all the groups which played at the Park, the John Philip Sousa Band enjoyed the best reception, and his musical reputation was built to a considerable extent on his appearances at Willow Grove Park. For the last twenty years during which these programs were offered, Sousa did not miss a single season, and was usually the final attraction, undoubtedly because of his drawing power. While other groups appeared for two weeks, Sousa usually stayed for four, and in 1922, when the average stand was lengthened to three weeks, Sousa was hired for five, from August 6 to September 10.

By this time, however, the age of the amusement park was swiftly passing. Improved roads and increasing numbers of automobiles, as well as the development of new means of entertainment such as the moving picture and the radio, drained much of the

business from the parks. There was little reason to ride a trolley to Willow Grove Park to hear music, when one could hear it in the privacy of his own home.

business from the parks. There was little reason to ride a trolley to Willow Grove Park to hear music, when one could hear it in the privacy of his own home.

The end of the era was marked by the sudden death of Victor Herbert in 1924, just prior to his engagement, scheduled for the entire month of June. Willow Grove was never the same again, and in 1926, the entire operation was leased to the orchestra leader, Meyer Davis, who attempted to operate it at a profit, something which PRT had never been able to accomplish.

There can be little question that Willow Grove Park contributed greatly to American music of the era. The pattern established there, of good music for a summer evening's listening, has been translated into such latter-day operations as Robin Hood Dell in Philadelphia. The Park provided the orchestra conductors and band leaders with an office in the band stand, in which was written some of the outstanding American music of the first quarter of the Twentieth Century. Victor Herbert, clad only in an undershirt, trousers and slippers, would sit at the piano by the hour, composing between performances, and pro. ducted some of his most famous works in Willow Grove. "Babes in Toyland" was written in its entirety at the Park, as was most of "The Red Mill." Herbert stated publicly that he would have never been able to find the time to write "The Red Mill" elsewhere, and that had it not been for the facilities at Willow Grove Park, the operetta would have remained unwritten.

John Philip Sousa also wrote much of his music at Willow Grove, and expressed his approval of the facilities. Sousa was a close friend of Thomas E. Mitten, who operated the PRT after 1911. His friendship was demonstrated on one occasion by the composition of the "March of the Mitten Men," an elaborate series of ruffles and flourishes which served as an introduction to a rousing arrangement of "Onward, Christian Soldiers." This contribution to musical literature was recorded by the PRT band for Victor, as one of the early "Orthophonic" recordings.

Sousa played annually for Mitten's PRT picnic. This was

originally an outing for the employes of the Company, but was quickly turned into a device for generating additional business at the Park, by throwing it open to the entire city of Philadelphia arid its surroundings.

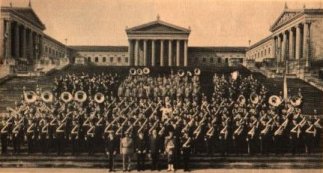

The picnic was conspicuously advertised. An advertisement, which has survived, carried on the front end of street cars in 1919, proclaimed in bold letters, "Mitten, Sousa, and Rodeheaver at our picnic." Homer Rodeheaver, musical director for the evangelist, Billy Sunday, and an accomplished singer and trombone player, usually led the singing. Mitten had a demonstrated partiality to brass bands, and organized both a PRT Marching Band and a bagpipe entourage known as the Kiltie Band, both of which performed at the picnics, along with Sousa and Rodeheaver.

The PRT management made no charge for attendance at the concerts in the Park. A writer for the North American who extolled the virtues of the Park in 1907 pointed out the high costs of the operation, and stated that over $65,000 was expended in 1906 for bands and orchestras. The reporter felt that this was an extremely generous gesture on the part of the PRT, as it permitted everyone to listen free of charge, regardless of whether they came to the Park on a PRT trolley or not. This generosity was, in the final analysis, a highly debatable thing, since PRT not only controlled all of the trolley lines into the Park, but also two of the chief turnpikes into Willow Grove.

The PRT management made no charge for attendance at the concerts in the Park. A writer for the North American who extolled the virtues of the Park in 1907 pointed out the high costs of the operation, and stated that over $65,000 was expended in 1906 for bands and orchestras. The reporter felt that this was an extremely generous gesture on the part of the PRT, as it permitted everyone to listen free of charge, regardless of whether they came to the Park on a PRT trolley or not. This generosity was, in the final analysis, a highly debatable thing, since PRT not only controlled all of the trolley lines into the Park, but also two of the chief turnpikes into Willow Grove.

Indeed, the Company collected more money per head from automobiles and bicycles using Old York Road than from trolley riders, with far less overhead, until the turnpike companies were sold to the state in 1918, and became part of the Pennsylvania state highway system. Since the decline of the fortunes of the Park, as we have already seen, was rapid after this time, it is conceivable that the turnpike business was the margin by which these rural operations prospered.

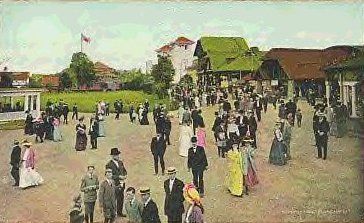

The music pavilion of the Park seated 5000 persons, and additional seating around the lake outside the pavilion permitted total seated crowds of 15,000, a number which was attained almost every night for the concerts. Often there were as many as 2000 to 3000 standees, and on Labor Day of 1905, a total of 52,000 people were on hand at the concerts. The afternoon crowds were largely women, the majority with children, while the evening crowds and those on Sundays were divided between

men and women.

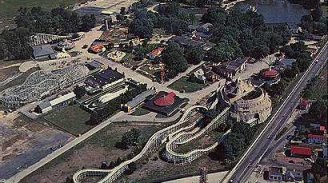

Music was but one of the attractions of the Park. It was equipped with an electric fountain which was claimed by the PRT to be the largest and finest of its type ever constructed. This was displayed at night, with varying colors of lights being played on the water spray in order to form constantly changing patterns.

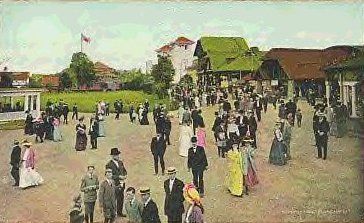

There were over one hundred amusement concessions, largely constructed during the rebuilding of the Park in 1904 and 1905. No vaudeville entertainment was provided, in keeping with the standards which the management tried to maintain, nor were there any outdoor attractions other than the music, the electric fountain, and a fireworks display on special occasions such as the Fourth of July.

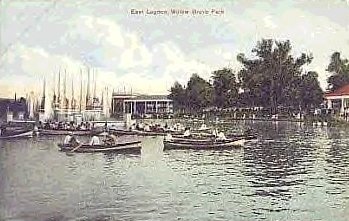

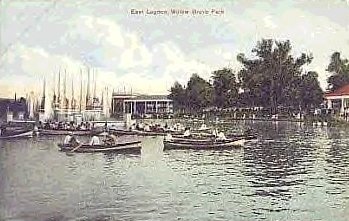

The largest of the lakes in the Park, which covered an area of four acres, was used for boating, and an electric launch and rowboats were available for those who wished to take to the water. The Park was illuminated at night with more than 50,000 electric lights, including incandescent lighting inside the buildings, and arc lights for the illumination of paths and picnic areas. The largest of the lakes in the Park, which covered an area of four acres, was used for boating, and an electric launch and rowboats were available for those who wished to take to the water. The Park was illuminated at night with more than 50,000 electric lights, including incandescent lighting inside the buildings, and arc lights for the illumination of paths and picnic areas.

The chief buildings were permanent structures, and were usually painted white. The administration building was a colonial style brick and stone structure which included the executive offices, information bureau, and a small hospital with a physician in permanent attendance.

The most spectacular ride was the roller coaster, which had a corporate structure as spectacular as the ride itself. When it was originally constructed in 1904-1905, it was classified as a railroad. Since the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company was permitted by its articles of incorporation and various other agreements to operate railroads but not to build them, the roller coaster was built by a wholly-owned dummy corporation, known as the L. A. Thompson Mountain Railway Company, probably the only roller coaster ever built with its own corporate organization. The mountain railway operated trains instead of individual cars as most amusement parks. It had an engineer with each train and block signalling along the route. In addition, there was a toboggan ride at the other end of the Midway. The chief buildings were permanent structures, and were usually painted white. The administration building was a colonial style brick and stone structure which included the executive offices, information bureau, and a small hospital with a physician in permanent attendance.

The most spectacular ride was the roller coaster, which had a corporate structure as spectacular as the ride itself. When it was originally constructed in 1904-1905, it was classified as a railroad. Since the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company was permitted by its articles of incorporation and various other agreements to operate railroads but not to build them, the roller coaster was built by a wholly-owned dummy corporation, known as the L. A. Thompson Mountain Railway Company, probably the only roller coaster ever built with its own corporate organization. The mountain railway operated trains instead of individual cars as most amusement parks. It had an engineer with each train and block signalling along the route. In addition, there was a toboggan ride at the other end of the Midway.

The Park was amply equipped with refreshment stands. The Casino was a restaurant located directly in front of the

music pavilion, where up to 500 persons could be served at one time on the open porches, while they listened to the music from the pavilion. The restaurant, unlike most of the concessions, was operated by the PRT management, and maintained high standards, with prices to match. In between pavilion concerts, small musical groups were on hand to play dinner music.

In addition, there were two light-lunch cafes, one in the upper part of the Park where the amusements were located, and one in the lower part, overlooking the lake and the electric fountain. A soda fountain was located in a separate building, and three picnic groves were scattered through the Park on the outer edge of the property. There was also a candy store, known, quite logically, as Candyland.

The major amusements were to be found between the toboggan and the L. A. Thompson Mountain Railway. These consisted of the Old Mill, the St. Nicholas Colliery,

a representation of a coal mine, the Venice exhibit, which gave a canal ride through what was reputed to be a faithful reproduction of a portion of that city, and the Willowgraph Theater. Smaller exhibits included a photograph gallery and a mirror maze, as well as an exhibit entitled Tours of the World.

A carrousel was located at each end of the Midway next to the rides, and a Ferris Wheel was located in the western part of the Park, at some distance from the other exhibits.

a representation of a coal mine, the Venice exhibit, which gave a canal ride through what was reputed to be a faithful reproduction of a portion of that city, and the Willowgraph Theater. Smaller exhibits included a photograph gallery and a mirror maze, as well as an exhibit entitled Tours of the World.

A carrousel was located at each end of the Midway next to the rides, and a Ferris Wheel was located in the western part of the Park, at some distance from the other exhibits.

The operation of such an undertaking required a considerable staff. During the regular season, the Park employed a staff of 500. It was largely self-sufficient, with its own sewage disposal plant, and greenhouses located behind the Willow Grove Car Barn at York and Davisville Roads. The Park was not inclosed by a fence, and patrons were free to come and go as they pleased. A main entrance was constructed, however, in the form of an underpass under Easton Road, which led directly from the Park to the trolley loading yard, which was opened in 1905.

Ironic as it may seem, Willow Grove Park does not seem to have been a financial success. As has been noted, patronage was disappointing in the first year, although it did account for an increase in traffic estimated at 70,000 persons. In 1905, in an article in the Street Railway Journal, the PRT noted that the Park yielded no profit to the Company, but that it was almost self-supporting. It was noted that the park had not been estab

lished by the current management, and after the experience of operating it, it was doubtful if the present operators would recommend the building of such a park, merely for the business which it would attract to the street car lines serving it. Since the Park existed, however, they had decided to maintain the highest standards in its operation.

The biggest problem in such an operation was the uneven crowds. As with morning and afternoon business rush hours, park traffic was an all-or-nothing proposition. In the winter, business consisted of that furnished by the local inhabitants, while in the Summer, as many as 20,000 people could leave the Park in the matter of a half an hour, after the end of the concerts. The result was the construction of massive facilities which received limited usage.

In order to serve the park traffic, it was necessary to maintain the power house at Ogontz, and another at Willow Grove, and a car barn at Willow Grove. In order to handle peak crowds,

it was necessary to build a special surface rail-way terminal at Willow Grove in 1905, which was one of the most elaborate installations of its kind in the world, yet was used only during the summer months, and unquestionably never returned even the original investment

To complicate the problem, the large crowds forced the purchase and operation of special equipment not suitable for normal traffic. A fleet of open trolley cars, not usable when the Park was closed, were required to service the line, and even such odd pieces as a group of sprinkler cars, which kept down the dust stirred up along the York Road by the passing cars, were required to maintain the service.

Peak traffic caused such short headways on the various lines serving the Park that serious operating problems were created. Even though York Road was a double-tracked trolley line, it was necessary to place warning block signals along the line, to warn of cars ahead at blind turns. The normal headway at this time could be as little as 30 seconds between cars, and any delays in operation could create a clear and present danger of a rear end collision.

it was necessary to build a special surface rail-way terminal at Willow Grove in 1905, which was one of the most elaborate installations of its kind in the world, yet was used only during the summer months, and unquestionably never returned even the original investment

To complicate the problem, the large crowds forced the purchase and operation of special equipment not suitable for normal traffic. A fleet of open trolley cars, not usable when the Park was closed, were required to service the line, and even such odd pieces as a group of sprinkler cars, which kept down the dust stirred up along the York Road by the passing cars, were required to maintain the service.

Peak traffic caused such short headways on the various lines serving the Park that serious operating problems were created. Even though York Road was a double-tracked trolley line, it was necessary to place warning block signals along the line, to warn of cars ahead at blind turns. The normal headway at this time could be as little as 30 seconds between cars, and any delays in operation could create a clear and present danger of a rear end collision.

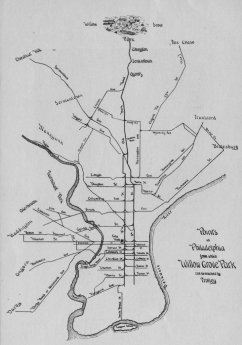

At its peak, a large number of trolley lines served the Park. The original line, which began operation in 1895, as has been noted, operated on 4th and 8th Streets in Philadelphia. It was numbered Route 55 in 1913, and re-routed to operate in Philadelphia on l0th and 11th Streets in that year. In 1929, when the Broad Street Subway was opened, it was cut back at the southern end to the Broad and Olney Terminal. Street car service above City Line was abandoned in 1941, when York Road was repaved and rebuilt. Rush hour service on the city portion of the line continued for another ten years.

In 1896, when the Park was opened, a second line was placed in service. This operated via York Road and Erie Avenue to 15th Street, operating on 15th and 13th Streets as far south as

Locust Street. This was probably the route which had been originally intended before Peoples Traction had gained control of the Company, and was now made possible by the merger of the properties of Philadelphia and Peoples Traction into the Union Traction Company. It was the first new line established by the Union Company. In 1913, during the general rearrangement of lines, it was numbered 24, and re-routed to run on 15th and 16th Streets. Declining business caused this line to be cut back to York Road and Cheltenham Avenue at its northern end in 1920.

Locust Street. This was probably the route which had been originally intended before Peoples Traction had gained control of the Company, and was now made possible by the merger of the properties of Philadelphia and Peoples Traction into the Union Traction Company. It was the first new line established by the Union Company. In 1913, during the general rearrangement of lines, it was numbered 24, and re-routed to run on 15th and 16th Streets. Declining business caused this line to be cut back to York Road and Cheltenham Avenue at its northern end in 1920.

Beginning in 1899, Chelten Avenue cars were routed over York Road to the Park when needed for supplementary service. Various routings were tried, some of which were unbelievably circuitous, in order to give direct service to the Park to the largest number of people. Even this did not satisfy everyone, and in 1912 we find a man bringing suit against PRT because they did not run a car on Germantown Avenue past his home, to take him directly to the Park.

Naturally, the various special routings set up to accomodate park traffic interfered with the schedules and orderly operation of the normal services. The routing of Chelten Avenue cars all the way to Willow Grove during peak traffic at the Park caused irregular headways and poorer service on the normal portion of the line.

By 1905, traffic was so heavy on York Road that it was proposed to build an entirely new line to the West of the existing line together with a new terminal at Willow Grove. The new line was built for the most part on private right of way, the portion within the city of Philadelphia being dedicated by PRT as Ogontz Avene. This new route was the Glenside line, and followed the route of the recently abandoned Route 6 north of City Line. The line operated over Chelten Avenue and Wayne Avenue into North Philadelphia, prior to 1929, since the tracks south of Chelten Avenue, even though constructed, were unconnected to any other line until 1929. The line was originally numbered Route 49, and began operation on May 15, 1905.

Simultaneously, the plan of operating cars around the outside of the Park, unloading at the north end of the Park, and loading along Easton Road, was abandoned. The new complex provided for twelve storage tracks for cars, and eleven loading platforms for outgoing passengers, an arrangement which could handle approximately 15,000 passengers hourly.

Since northbound traffic was not subject to the peak loads characteristic of traffic leaving the Park, the facilities designed for handling this traffic were somewhat simpler. After construction of the new terminal, regular passenger cars were no longer operated in the Park. However, freight cars continued to run through the property, since the Willow Grove freight house, built about 1910, was located on the Old Welsh Road, at the southern end of the Park, and could be reached only by the loop track through the Park.

Willow Grove Park never recaptured the splendor of the years prior to World War I, and gradually declined in prestige and prosperity after its management passed into private hands. The large tract of land which had been used as a picnic grove and park north of New Welsh Road, and the complex including the greenhouses, power house, and car barn, were sold to real estate developers who erected

shopping centers. With the abandonment of the Route 6 trolley in 1958, the land occupied by the old terminal was sold, again for the erection of stores. About the same time, the lake area to the South of New Welsh Road (now known as Moreland Road), was sold for the construction of a large bowling alley.

shopping centers. With the abandonment of the Route 6 trolley in 1958, the land occupied by the old terminal was sold, again for the erection of stores. About the same time, the lake area to the South of New Welsh Road (now known as Moreland Road), was sold for the construction of a large bowling alley.

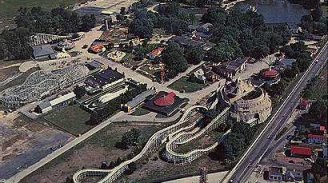

Today Willow Grove Park is but a shadow of its former self. The music is gone, and the surviving portion of the Park centers on the old amusement gallery complex erected in 1905. The L. A. Thompson Mountain Railway still operates, as do other rides constructed in later years, but the electric fountain is gone, and the reflecting pool in front of the bowling alley gives only a hint of the glory of a by-gone era.

There are those who will say that the decline of such institutions as Willow Grove Park is a by-product of progress, and that such progress is beneficial. This writer, longing for a day of leisurely and gracious living which seems to have gone forever, cannot agree.

1 (An early attraction at Willow Grove not mentioned by Dr. Cox was a large oval wooden bicycle racing track, located somewhere near the Old Welsh Road. Bicycle races of national importance were held here during the last half of the 1890's. - Editors)

Return to Learn More

|

|

Peoples Traction Company, secured an overlapping franchise from Erie Avenue to Broad and Olney only four days later. It appeared that the competition for the route could easily lead to acts of violence, as it already had elsewhere in Philadelphia, if both companies decided to begin construction simultaneously.

Peoples Traction Company, secured an overlapping franchise from Erie Avenue to Broad and Olney only four days later. It appeared that the competition for the route could easily lead to acts of violence, as it already had elsewhere in Philadelphia, if both companies decided to begin construction simultaneously. usual in most American cities.

Willow Grove Park was opened for the 1896 season, and immediately generated additional traffic, although not nearly as much as the management had hoped. Deciding that still greater attractions were needed, in 1897 the Union Traction Company (Peoples Traction having been taken over the previous year), decided to institute regular music programs in the Park, and hired the New York Symphony Orchestra to come to Willow Grove and play the entire season in the band shell, under the direction of its conductor, Walter Damrosch. So popular was this feature that it was retained, and the musical presentations of the Park became its most famous attraction.1

usual in most American cities.

Willow Grove Park was opened for the 1896 season, and immediately generated additional traffic, although not nearly as much as the management had hoped. Deciding that still greater attractions were needed, in 1897 the Union Traction Company (Peoples Traction having been taken over the previous year), decided to institute regular music programs in the Park, and hired the New York Symphony Orchestra to come to Willow Grove and play the entire season in the band shell, under the direction of its conductor, Walter Damrosch. So popular was this feature that it was retained, and the musical presentations of the Park became its most famous attraction.1 business from the parks. There was little reason to ride a trolley to Willow Grove Park to hear music, when one could hear it in the privacy of his own home.

business from the parks. There was little reason to ride a trolley to Willow Grove Park to hear music, when one could hear it in the privacy of his own home.

a representation of a coal mine, the Venice exhibit, which gave a canal ride through what was reputed to be a faithful reproduction of a portion of that city, and the Willowgraph Theater. Smaller exhibits included a photograph gallery and a mirror maze, as well as an exhibit entitled Tours of the World.

A carrousel was located at each end of the Midway next to the rides, and a Ferris Wheel was located in the western part of the Park, at some distance from the other exhibits.

a representation of a coal mine, the Venice exhibit, which gave a canal ride through what was reputed to be a faithful reproduction of a portion of that city, and the Willowgraph Theater. Smaller exhibits included a photograph gallery and a mirror maze, as well as an exhibit entitled Tours of the World.

A carrousel was located at each end of the Midway next to the rides, and a Ferris Wheel was located in the western part of the Park, at some distance from the other exhibits. it was necessary to build a special surface rail-way terminal at Willow Grove in 1905, which was one of the most elaborate installations of its kind in the world, yet was used only during the summer months, and unquestionably never returned even the original investment

To complicate the problem, the large crowds forced the purchase and operation of special equipment not suitable for normal traffic. A fleet of open trolley cars, not usable when the Park was closed, were required to service the line, and even such odd pieces as a group of sprinkler cars, which kept down the dust stirred up along the York Road by the passing cars, were required to maintain the service.

Peak traffic caused such short headways on the various lines serving the Park that serious operating problems were created. Even though York Road was a double-tracked trolley line, it was necessary to place warning block signals along the line, to warn of cars ahead at blind turns. The normal headway at this time could be as little as 30 seconds between cars, and any delays in operation could create a clear and present danger of a rear end collision.

it was necessary to build a special surface rail-way terminal at Willow Grove in 1905, which was one of the most elaborate installations of its kind in the world, yet was used only during the summer months, and unquestionably never returned even the original investment

To complicate the problem, the large crowds forced the purchase and operation of special equipment not suitable for normal traffic. A fleet of open trolley cars, not usable when the Park was closed, were required to service the line, and even such odd pieces as a group of sprinkler cars, which kept down the dust stirred up along the York Road by the passing cars, were required to maintain the service.

Peak traffic caused such short headways on the various lines serving the Park that serious operating problems were created. Even though York Road was a double-tracked trolley line, it was necessary to place warning block signals along the line, to warn of cars ahead at blind turns. The normal headway at this time could be as little as 30 seconds between cars, and any delays in operation could create a clear and present danger of a rear end collision. shopping centers. With the abandonment of the Route 6 trolley in 1958, the land occupied by the old terminal was sold, again for the erection of stores. About the same time, the lake area to the South of New Welsh Road (now known as Moreland Road), was sold for the construction of a large bowling alley.

shopping centers. With the abandonment of the Route 6 trolley in 1958, the land occupied by the old terminal was sold, again for the erection of stores. About the same time, the lake area to the South of New Welsh Road (now known as Moreland Road), was sold for the construction of a large bowling alley.